Hidden tragedies, hidden truths (because, in literary criticism, the truth is *always* where you put it)

Disclaimer:

This is more than usually not-completely serious. At least, for such a dark topic, it comes in from an overly sunny backwards angle, with a cheek full of tongue. It gets more serious later, but it doesn’t qualify for the role of a “useful resource” so be warned. By way of all the apology you’re getting, I’ve scattered the latter half of the post with semi-random helpful links, just in case it sets you thinking. Stick with them for the genuine advice; stay here if you’re well-enough off that you can afford the luxury of me amusing myself with a sort-of thought experiment in misusing critical thinking.

Benefits of listening to Jack? It’s better than a poke in the eye. And we don’t repeat a single song in the workday– Jack FM.

Disadvantages: sometimes they play things that suck (they just do it a lot less than some what I could mention). So it was that today I got stuck listening to Kate Nash’s Foundations again. Which has always struck me as a soulless, naïve sort of a song. In the event you’ve happily skipped it, you can catch up with it here:

See? I’m pretty sure I ain’t copping any blame for thinking that was staggeringly shallow. Holding onto the cracks? What good is that meant to do, you inflectionless moron?

…Or so I thought. But then I realised I wasn’t listening closely enough: it’s not just holding onto cracks, but specifically, the cracks in our [relationship’s] foundations. Which begs the question, ‘what good is that meant to do, you inflectionless moron?’

Answer: none at all. On account of this isn’t the shallow pap initially suggested by the surface tone of the song, but is actually quite a clever piece about someone trapped in an abusive relationship.

If this comes as no surprise at all, I apologise, but you need to understand that my reaction to Remains of the Day was something like ‘Yay Stevens! Nuts to Miss Kenton, she’s a disloyal flake, and you’re better off without the feckless cow. Better to go back home and see if you can’t train that slacker Faraday to behave in a manner more befitting! “Banter” indeed…’ Which, they tell me, slightly misses the point somehow… .

Anyway, I offer that by way of demonstrating that I generally show too much faith to notice an unreliable narrator on the first couple of passes, and it took me several encounters with the song to realise that the narrator is not the wronged woman she claims, but is a manipulative and vicious sociopath. It’s very well done, I’ve got to say. The hints are there, but you have to separate them from the backdrop of imagined injuries the narrator thrusts to the fore of her narrative.

At this point it’s also worth noting the delivery of the song, which remains static throughout the tale: short, broken sentences, delivered in an almost always level, consistent voice. This is a narrator working hard to control the story they’re telling, carefully regulating the words they offer us, even at the expense of their fluidity of expression. In itself, this is disturbing; it’s not the watchfulness of someone struggling to frame their words through their emotions, but of someone carefully taking notes of how she covers each event. More alarming, though, is the subtext to that coverage, which is what I’d like to focus on, because the surface deceit speaks well enough for itself.

Let’s examine the first stanza for a moment:

Thursday night, everything’s fine, except you’ve got that look in your eye / when I’m tellin’ a story and you find it boring / you’re thinking of something to say. / You’ll go along with it then drop it and humiliate me / in front of our friends. / Then I’ll use that voice that you find annoyin’ and say something like / “yeah, intelligent input, darlin’, why don’t you just have another beer then?” / Then you’ll call me a bitch and everyone we’re with will be embarrassed, / and I wont give a shit.Not quite an average night out. Our narrator and her nameless partner are somewhere – most likely in a pub, although the reconstructed vision in the music video confines us to a significantly domestic setting – with some friends, and she is telling an anecdote. He listens along, thinking of ways he can add to the conversation. When she has finished speaking (after he has “gone along with it”) he “drops in” his contribution. Note that we do not know what this contribution is, only that the narrator feels “humiliated”.

I suggest that, in the absence of any indicators to the contrary, the narrator is humiliated because the focus of conversation has moved away from her. She told this story, the focus should be on her! Not on her partner, but on her, always her. (The video, you’ll note, continues this theme, barely showing us the partner at all: the focus is always on the narrator, or on inanimate objects stop-motioned into puppetry to support her narrative). Self-centred as our narrator is, the only way she can retrieve the focus in this specific instance is to belittle her partner, and so she mocks him, not only his immediate conversational input, but also his aspirations to further participation in her social activities.

He retaliates, attempting to put her down in a reflexive response to the genuine humiliation and hurt she has dealt him: he calls her a bitch. Like any normal people, the friends are embarrassed. We can take it as read that the narrator’s partner is embarrassed – humiliated again – as an immediate consequence of his misguided attempt to assert himself but “she won’t give a shit”. It isn’t that she is oblivious to the awkwardness, but that she does not care about the welfare and comfort of her friends.

The syntax is significant, here: we move from a narrative account of what will happen (“You are thinking”, “You will go along,” I will use that voice”) to a sudden negation (“I will not give a shit”). The change is unexpected and jarring, just as her (lack of) reaction is unexpected and jarring. Subtly, the narrator has placed herself outside of both the cultural and narrative norms. Beyond that, the assertion “won’t” has its own significance, since it implies not a lack of ability (can/cannot) but a lack of capacity (will/will not): the payoff isn’t there, and so her friend’s comfort is not worth her time or effort.

I want to skip over the chorus at this point, because I think it deserves separate examination of its own. Instead, let’s take a look at the second stanza:

You said I must eat so many lemons ’cause I am so bitter. / I said “I’d rather be with your friends mate ’cause they are much fitter.” / Yes, it was childish and you got aggressive, and I must admit that I was a bit scared

but it gives me thrills to wind you up.

This is a significant break from the rhythm of the main narrative: the accusation of bitterness has genuinely got to the narrator, and she unconsciously emphasises her riposte “fitter” and also lets slip a key clue to her motives: “it gives [her] thrills” to treat her partner in this way.

Again, there’s a tension between the surface presentation of events and what’s actually happening – a constant theme of the song, continually re-enforced in the accompanying video, with it’s ongoing undertones of physical violence; acts of hand-slapping, arm-wrestling, shadow-boxing and foot-kicking that are never referenced through the narrator’s voice, but which we see her initiate from the corner of her mind’s eye as she reconstructs reality around our listening ear.

Notice that whilst the lyrics claim the partner got aggressive, “scaring” our narrator, actual detail on the aggression is scant. In such a litany of woe, is this not surprising? The narrator is more than happy to list every other fault her partner has, so why shy away so quickly from details of his aggression? More than that, why is she “a bit scared” by this aggression? One would expect mid-argument aggression to be genuinely scary, not merely “a bit” scary, otherwise it would not be particularly memorable (especially in such a dysfunctional, hostility-prone relationship as the narrator happily admits this to be).

I suggest the only reason is not that the aggression did not happen, but that it was not ‘aggression’ in the way the word is normally used. Rather it is assertion: ‘Why don’t you, then?’ he may have said, or ‘I don’t care – if you don’t love me, I should leave you anyway.’ Once we have realised her barbs have caused him to become assertive, her fear makes sense: she does not become ‘a bit scared’ because of aggression, but because she can see her control of her partner momentarily – and only temporarily – slip. Again, our narrator cannot abide the loss of control, and so her ongoing need for control is at one and the same time the reason for her fear, and also for the minimal nature of it. She is scared, but only a bit: the loss of control frightens her ego, but she remains confident that her control of her partner is stronger than the little will to fight she has left him, and that confidence mutes not only her fear, but also her partner, whom she carefully deprives of speech from hereon.

Indeed, as her partner’s voice is carefully edited out of the narrative, so does the narrator become more aggressive; the slight glimpses of her violent nature we have seen so far begin to give way to actual neglect, as in the third and final verse:

Your face is pasty ’cause you’ve gone and got so wasted, what a surprise. / Don’t want to look at your face ’cause it’s makin’ me sick. / You’ve gone and got sick on my trainers, I only got these yesterday. /

Oh, my gosh, I cannot be bothered with this. /

Well, I’ll leave you there ’till the mornin’, and I purposely wont turn the heating on / and dear God, I hope I’m not stuck with this one.Here we see the narrator shift responsibility away from herself. I do not object to accepting that he “has gone” and got drunk (the nature of the narrator’s sociopathic tendancy seems to be towards the embellishment of facts in her favour, rather than towards their complete fabrication), but notice how his desire to drink excessively is presented in a vacuum, divorced from their relationship. Indeed, it only becomesrelevant to the narrator when he is sick on her trainers (although whether as a genuine accident or as his last subconscious act of defiance we will never know).

Her reaction (predictably) is both disproportionate and chilling. Since her partner has been sick she cannot pretend that his drunkenness is not serious, but rather than seeking to make him as comfortable as she can (whether by helping him to the bathroom, or by offering him a glass of water) she instead seeks to make him uncomfortable, leaving him where he is and “purposely” not turning on the heating – implying both the deliberation put into the weighing-up of her actions, and the purpose (of punishing him) with which she neglects his wellbeing.

Far, far, darker is the closing line of the verse, “Dear God, I hope I’m not stuck with this one”. On the surface, perhaps we could yet be persuaded that this is a cry for help, from a woman who wants out of her relationship, but somehow can’t effect an exit. But that doesn’t fit with the rest of her attitude, which even on the surface level paints her as an assertive person (for example, the deliberate antagonism of “that voice” and the childish taunting about his “fitter” friends, which fail to support the theory she is the cowed member of the relationship).

That leaves us with three basic options: that she hopes to drive him away (again, shunning responsibility for her actions), that she’s hoping to snare another man behind his back, and then throw him out (but in the meantime, she is willing to risk getting “stuck” for the security and control of an ongoing relationship, in contrast to the uncertain, uncontrolled chaos of being ‘single and looking’) or – in an interpretation far more fantastic, but still not particularly out of character – that he will quietly die in the night, choking to death unheeded, in a freezing mire of his own sick.

Disturbing indeed. About the only thing remaining is the chorus, and that’s where things get really interesting, and the narrator allows a faint chink of humanity to glimmer through her workaday sadism:

My fingertips are holding onto /

The cracks in our foundation /

And I know that I should let go, but I can’t /

And every time we fight, I know it’s not right /

Every time that you’re upset and I smile /

I know I should forget, but I can’t.

The first two lines of the chorus are what clued me into the real meaning of this song, because nobodywould hold onto a crack in a foundation. A foundation, as any fule kno, is the underlying structure which exists to hold up something much bigger than itself. A well-built foundation will spread the load of the building above, ensuring that all of the weight is distributed downwards, and helpfully provide stability to the whole structure, even if part of the foundations cover a patch of bad or unstable ground. Foundations might crack, and this is a cause for concern, but the solution to cracking foundations is to patch them up again, not break out your finest Dutchboy impression.

Thus the only reason to stick your fingernails into the cracks would be to agitate the bears pry the cracks open wider. That, and the hidden-in-plain-sight viciousness of smiling at her partner’s misery, is what helped me to realise what a horrible bitch the narrator is. Once you revisit the song on that understanding, it’s pretty obvious that the narrator is lying through her teeth the whole time.

Brilliantly, Nash casts us, the unknown listener, in the role of the narrator’s boyfriend, forcing the casual listener to dole out sympathy when the actions she ascribes to us trigger unease: we are so busy thinking how awful it would be if we treated our partners as her boyfriend ‘does’ that we do not stop to make a closer investigation of the facts.

And yet, Nash wants us to find the narrator out, and invests her with just the faintest glimmer of self-awareness: “I know that I should let go, but I can’t“. She knows this is wrong, that normal people do not treat their partners in this way, but she literally can’t help herself. Even though she knows herself to be at fault, she still inflicts misery on her boyfriend, because she is incapable of anything else. Abusers do not change, even when they express awareness and contrition.

(Usually. What I mean is ‘abusers rarely change,’ but that reduces the impact of the preceding line. Since this is actually important, however, I’m sacrificing narrative pace for the dissemination of more accurate information).

The whole song is brilliant, because it works on so many levels, with a different message to each level.

- On the surface, it appears to tell of a woman trapped in a loveless partnership, which may even be abusive. (See all the little ways in which abuse grinds her down)

- On closer viewing, we realise that she is the abuser (If you suspect someone is in an abusive relationship, do not let their partner speak for them).

- Which means her boyfriend is the victim (Men can also be victims of domestic violence at the hands of male or female partners. When this happens, it is harder for them to be heard – qv the assumption we made in the first bullet point)

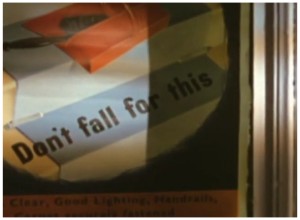

The video is even cleverer: the narrator packs her suitcase, takes a last look around the flat, and leaves. As the door closes, the camera remains static and we see the poster on the back of the door: “Don’t Fall For This” – suggesting, on the first level, that the poster is what the narrator thinks (ie, do not fall into the trap of a loveless or abusive relationship), but actually possessing three other meanings: firstly, do not fall for the lies this abuser has told you, secondly, do not fall for someone like this, and thirdly, do not fall for the perception that domestic abuse only affects women.

As a guerrilla awareness campaign, I’ve got to say Foundations is genius. From showcasing the subtle digs that together form a pattern of emotional abuse, to the pattern of escalation and the parallel silencing of the abused boyfriend and the sudden jolt you get when you realise that all you’ve heard so far is a lie designed to protect the narrator from her lack of control (and the subsequent questions that might raise about other couples you know) the whole song forms a brilliantly subtle protest against domestic abuse.

Even sweeter, is the way it is disguised as a mirror of itself: it sounds like a song about an abusive relationship – and it is – but you were looking in the wrong place. That, above all, elevates Foundations to the level of genuine Art, with the screamingly hidden message we should all be aware of, and willing to speak out against, domestic abuse, in all of its forms.

So, there you go, the true meaning of Foundations. You’d have thought people would have clocked it already, except I expect most people have better things to do than sit around stubbornly over-interpreting a fleeting scrap of quasi-popular culture until it breaks. Which is a shame, because it’s actually quite fun. (Plus, if the profiling doesn’t pan out, I won’t need more than another couple of posts like this to get myself a snazzy book deal with Cambridge Scholars some publisher of unconsidered trifles…)

Hm. A post that ended up feeling heavier than it should have been, probably. But, genuinely, I think it’s a good song for the above reasons (because even thought it’s probably not what Nash thought it was saying, it’s what it could be saying, and that works pretty well. ‘s the magic of –Criticism and Interpretation, that is).

Still, by way of some light relief, here is a funny comic about domestic abuse, which Dan shared a week or so back…

Comments

Wow. That’s an incredible bit of analysis, wonderfully-presented, and an awesome blog post in general. Suddenly, one just feels the urge to shout “DTMFA” at the narrator’s partner. For all the good it’d do.

This post (and now – for a little while, I expect – the song) also makes me quite uncomfortable. As what might be described as a former victim of domestic abuse, there’s a particular significance to the coded messages in that song. How would (did!) my abuser appear to the outside world? Sometimes, exactly as the song’s narrator does (try to): as the “injured party” in a toxic relationship, who should leave but can’t bear to. I remember on one occasion, towards the end of our relationship, that she complained about me to a friend of ours (mine, really, just to rub it in) who then took her side, contacting me to say “Why are you treating [her] this way?” For somebody like me, desperate for someone to notice what was going wrong but unable to ask for help himself, to have somebody take the other side was heartbreakingly demoralising. But given the context of the song you’ve just disassembled, it’s pretty easy to see how the mistake could have been made.

From the outside, it’s not always easy to see domestic abuse; especially where the abusive partner is the one who speaks for both of them. Domestic abuse does not require physical violence, and even physical violence does not necessarily require that one partner is necessarily stronger than the other. Yet despite having learned these lessons many years ago, I didn’t for a moment make the interpretation of that song that you have done, and that makes me feel complicit.

Now I feel sad.

Still an awesome blog post, though. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

If it helps any, it’s not the sort of interpretation people naturally make about songs. I got there because I was amusing myself by tearing the chorus to bits in my head (because I like to punish badly expressed songs, and whilst the foundations line really isn’t “We So Excited” bad, it’s still more grating than “Are We Human Or Are We Expressing A False Dichotomy Badly”.

It’s just once I took a look from that perspective, everything started lining up, and that was sufficiently creepy that I thought it was worth expanding on, and once I started expanding on it, it felt like there was a genuinely good point in there about not taking stuff at face value once the stakes get that high.

Didn’t know that, btw. Apologies for starting your day with a downer…

No worries. It’s a good blog post.

I’d like to think that your interpretation is correct. That said, I’m not sure that I credit Nash with sufficient intelligence to have written it that way herself, and – without the clues from the music video – it’s possibly just a string of co-incidences… so it could just be that there’s a clever producer/editor, somewhere. But maybe, maybe…

Sorry; assumed you were up-to-date anyway: it’s no secret from you guys. Anyway – it’s still a good blog post that I appreciated reading. Just a sad one, too. Keep writing!